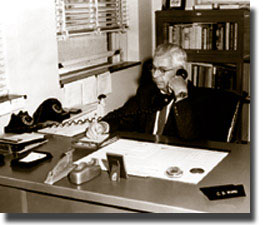

Becoming the first hospital administrator gave

Claude D. "C.D." Ward a new career he then used to help give Pitt

County a new hospital.

![]() Ward

left behind the familiar world of a high-school principal to accept the post

of administrator in 1942, when Greenville was mostly farmland and the concept

of a true public hospital was years away. Most roads were cart or footpaths;

in the summer, tobacco fields spread like a green sea broken by peaks of curing

barns. The Johnston Street hospital, known as Pitt General, had only 42 beds.

Ward

left behind the familiar world of a high-school principal to accept the post

of administrator in 1942, when Greenville was mostly farmland and the concept

of a true public hospital was years away. Most roads were cart or footpaths;

in the summer, tobacco fields spread like a green sea broken by peaks of curing

barns. The Johnston Street hospital, known as Pitt General, had only 42 beds.

![]() To

his role, Ward brought energy, warmth and a genuine concern for patients.

He also brought the people skills he learned as a top school administrator:

He was engaged with his staff and with their affairs, learning about healthcare

and making sure he was part of its decisions. He signed checks, hired staff

members and kept purchasing records.

To

his role, Ward brought energy, warmth and a genuine concern for patients.

He also brought the people skills he learned as a top school administrator:

He was engaged with his staff and with their affairs, learning about healthcare

and making sure he was part of its decisions. He signed checks, hired staff

members and kept purchasing records.

![]() After

the second World War, a program to provide communities with federal money

for hospital construction, known as the Hill-Burton Act, made it possible

to make healthcare a public priority- and remedy a shortage of hospitals.

During Ward's tenure, plans took shape for a new hospital to be built on Fifth

Street. In the winter of 1951, the hospital opened, christened Pitt County

Memorial Hospital.

After

the second World War, a program to provide communities with federal money

for hospital construction, known as the Hill-Burton Act, made it possible

to make healthcare a public priority- and remedy a shortage of hospitals.

During Ward's tenure, plans took shape for a new hospital to be built on Fifth

Street. In the winter of 1951, the hospital opened, christened Pitt County

Memorial Hospital.

![]() In

this larger, more complex institution Ward retained his open manner, a trait

that seems to have characterized the organization. Most employees knew each

other by name and Ward kept tabs on everyone. He even set up an intercom to

talk to them and some say, listen in on them, as well.

In

this larger, more complex institution Ward retained his open manner, a trait

that seems to have characterized the organization. Most employees knew each

other by name and Ward kept tabs on everyone. He even set up an intercom to

talk to them and some say, listen in on them, as well.

![]() He

also made sure the hospital operated despite the difficult financial times.

John Stallings, one of the hospital's first pharmacists, said that during

his employment interview, Ward was firm about salaries.

He

also made sure the hospital operated despite the difficult financial times.

John Stallings, one of the hospital's first pharmacists, said that during

his employment interview, Ward was firm about salaries.

![]() "The

negotiations were quite interesting," Stallings said, looking back to

the interview in 1969. Now a pharmacy administrator, Stallings was set to

graduate from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill when he decided

to come to Greenville.

"The

negotiations were quite interesting," Stallings said, looking back to

the interview in 1969. Now a pharmacy administrator, Stallings was set to

graduate from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill when he decided

to come to Greenville.

![]() "Mr.

Ward and I sat down and he told me what the salary was going to be, and I

tried to talk him into just a little bit more. He said if I didn't like it,

he had several other people who were interested, and that was the end of the

conversation. It was tough to negotiate with him."

"Mr.

Ward and I sat down and he told me what the salary was going to be, and I

tried to talk him into just a little bit more. He said if I didn't like it,

he had several other people who were interested, and that was the end of the

conversation. It was tough to negotiate with him."

![]() At

the same time, Ward was open minded and just, said Bill Young,

At

the same time, Ward was open minded and just, said Bill Young,

administrator for Special Medical Services.

![]() "If

you wanted anything like equipment, or to do something different, everything

went through him. If he said, 'Ok,' it was a done deal. He was not a real

big negotiator, but he was fair. I never went to him and laid things out that

I didn't feel like he listened. I thought he was a very fair individual."

"If

you wanted anything like equipment, or to do something different, everything

went through him. If he said, 'Ok,' it was a done deal. He was not a real

big negotiator, but he was fair. I never went to him and laid things out that

I didn't feel like he listened. I thought he was a very fair individual."

![]() Nurse

Hilda Norris remembered how Ward responded when he found his desk lamp in

the nursery. Ms. Norris took it there to shine on babies to help them break

down bilirubin, a blood substance associated with jaundice. "The first

bili light was put in because I went into Mr. Ward's office and took his lamp

off his desk," she said. "I was in his office and saw this big light,

so I just unloaded it and walked out. Several weeks later he found it and

he came and laughed."

Nurse

Hilda Norris remembered how Ward responded when he found his desk lamp in

the nursery. Ms. Norris took it there to shine on babies to help them break

down bilirubin, a blood substance associated with jaundice. "The first

bili light was put in because I went into Mr. Ward's office and took his lamp

off his desk," she said. "I was in his office and saw this big light,

so I just unloaded it and walked out. Several weeks later he found it and

he came and laughed."

![]() When

he stepped down in 1971, several staff members prepared a surprise for him.

Inside a doll dressed to resemble him, he found a roll of money totaling $1,000

to send him into his next career as a retired hospital pioneer.

When

he stepped down in 1971, several staff members prepared a surprise for him.

Inside a doll dressed to resemble him, he found a roll of money totaling $1,000

to send him into his next career as a retired hospital pioneer.

C. D. Ward

The Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University

600 Moye Boulevard

Greenville, North Carolina 27858-4354

P 252.744.2240 l F 252.744.2672